This post originally appeared at Market Urbanism, a blog about free-market urban development.

After receiving years of praise for its work in post-Katrina recovery, Brad Pitt’s home building organization, Make It Right, is receiving some media criticism. At the New Republic, Lydia Depillis points out that the Make It Right homes built in the Lower Ninth Ward have resulted in scarce city dollars going to this neighborhood with questionable results. While some residents have been able to return to the Lower Ninth Ward through non-profit and private investment, the population hasn’t reached the level necessary to bring the commercial services to the neighborhood that it needs to be a comfortable place to live.

After Hurricane Katrina, the Mercatus Center conducted extensive field research in the Gulf Coast, interviewing people who decided to return and rebuild in the city and those who decided to permanently relocate. They discussed the events that unfolded immediately after the storm as well as the rebuilding process. They interviewed many people in the New Orleans neighborhood surrounding the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church. This neighborhood rebounded exceptionally well after Hurricane Katrina, despite experiencing some of the city’s worst flooding 5-12-feet-deep and being a low-income neighborhood. As Emily Chamlee-Wright and Virgil Storr found [pdf]:

Within a year of the storm, more than 3,000 residents had returned [of the neighborhood's 4,000 residents when the storm hit]. By the summer of 2007, approximately 90% of the MQVN residents were back while the rate of return in New Orleans overall remained at only 45%. Further, within a year of the storm, 70 of the 75 Vietnamese-owned businesses in the MQVN neighborhood were up and running.

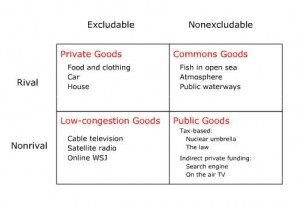

Virgil and Emily attribute some of MQVN’s rebuilding success to the club goods that neighborhood residents shared. Club goods share some characteristics with public goods in that they are non-rivalrous — one person using the pool at a swim club doesn’t impede others from doing so — but club goods are excludable, so that non-members can be banned from using them. Adam has written about club goods previously, using the example of mass transit. The turnstile acts as a method of exclusion, and one person riding the subway doesn’t prevent other passengers from doing so as well. In the diagram below, a subway would fall into the “Low-congestion Goods” category:

In the case of MQVN, the neighborhood’s sense of community and shared culture provided a club good that encouraged residents to return after the storm. The church provided food and supplies to the first neighborhood residents to return after the storm. Church leadership worked with Entergy, the city’s power company, to demonstrate that the neighborhood had 500 residents ready to pay their bills with the restoration of power, making them one of the city’s first outer neighborhoods to get power back after the storm.

While resources have poured into the Lower Ninth Ward from outside groups in the form of $400,000 homes from Make It Right $65 million in city money for a school, police station, and recreation center, the neighborhood has not seen the success that MQVN achieved from the bottom up. This isn’t to say that large non-profits don’t have an important role to play in disaster recovery. Social entrepreneurs face strong incentives to work well toward their objectives because their donors hold them accountable and they typically are involved in a cause because of their passion for it. Large organizations from Wal-Mart to the American Red Cross provided key resources to New Orleans residents in the days and months after Hurricane Katrina.

The post-Katrina success of MQVN relative to many other neighborhoods in the city does demonstrates the effectiveness of voluntary cooperation at the community level and the importance of bottom-up participation for long-term neighborhood stability. While people throughout the city expressed their love for New Orleans and desire to return in their conversations with Mercatus interviewers, many faced coordination problems in their efforts to rebuild. In the case of MQVN, club goods and voluntary cooperation permitted the quick and near-complete return of residents.